Science Fiction and Why It’s Great – Part 2

Sometimes writing is dangerous. Throughout history writers have sometimes had to hide their meaning behind symbolism and metaphor, for to say openly what they really meant could easily mean persecution or death. Thankfully this isn’t the case too often in modern Western culture, but even in our relatively open and tolerant society, writers sometimes choose, for a variety of good reasons, to mask their thoughts in allegory. Science fiction is tailor-made for this sort of hidden meaning, and this is the second reason why it’s great.

There are some well-known examples of sci-fi stories taking on social or political issues, and George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four is perhaps the most famous of all. His portrayal of a ruthlessly oppressive society resonated deeply with the anti-Communist hysteria of the Cold War, but even today the reader is chilled by the manipulation and control imposed upon virtually helpless members of society. A modern reader might even see in it a reflection of our media-dominated, superficial popular culture just as easily as a paranoid Red-hunter would have spotted Uncle Joe in the 50’s.

Science fiction, by its very nature, takes place in a world that is somehow different from ours. It could be set far in the future, or on a distant world, or in downtown Seattle where magic is real. This ability of the genre to exist as close to, or as far away from, our real world as the author wants gives it a unique ability to comment on the human condition. If an author wants to comment on the dangers of genetic engineering, he might have a modern-day lab bring prehistoric creatures to life, like Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park. If instead the author wants to explore human mortality he might do so with robots like Isaac Asimov in his I, Robot collection. Or an author could provide unique insight into the wisdom of the elderly by giving his aged characters powerful new bodies as John Scalzi did in Old Man’s War. In every case, the science fiction author has the freedom, if she so chooses, to explore complex and insightful aspects of our humanity without necessarily getting bogged down in real-world politics or potentially divisive issues.

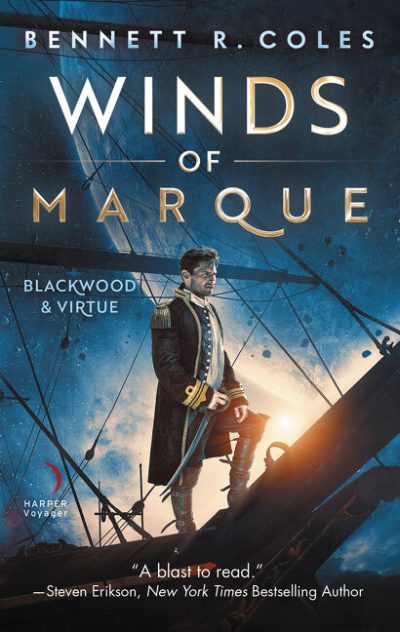

In my first novel, Virtues of War, one of the themes I wanted to explore was this: what is it really like to be a soldier? What happens psychologically to regular men and women when they see combat for the first time? And what are the very real consequences of the split-second decisions they make under extreme stress? As a military veteran it’s an idea dear to my heart, but the last thing I wanted to do was set the story in a modern day conflict like Afghanistan or Iraq. I have no interest in wading into the reasons behind why those real wars started, nor do I have any interest in taking sides. My story isn’t about the reasons for war, nor is it about either American or Arab grievances. My story is about the people: it’s about the soldiers. I certainly drew on my real-life experiences in Syria and Lebanon, but by setting Virtues of War nearly 500 years in the future and on another world, I freed myself from any real-life cultural baggage that could easily have accompanied my desired theme.

Being allegorical, a science fiction story can endure far beyond what the author originally intended. Just as Nineteen Eighty-Four has outlived the political movement that inspired it, perhaps James Cameron’s Avatar will still resonate long after the dangers of reckless environmental exploitation have faded to a happy irrelevance. Not only does this give science fiction a potential for longevity not necessarily enjoyed by other genres, it only adds to the broad appeal it already commands.

So that’s the second reason why science fiction is great: it provides the perfect vehicle for the pure exploration of real and relevant aspects of the human condition without causing offense. Or to put it in a less pompous way: science fiction is not only cool, it makes you think.